- A helping hand for hands

- A new battery of easy and painless tests may help spot workers at risk for serious hand injuries.

Radwin says new computer tests to detect carpal tunnel syndrome are "simple to administer and painless."

The numbing pain of carpal tunnel - caused by an entrapment of the median nerve in the wrist - is a common complaint of computer users, but it is also prevalent among workers who perform repetitive tasks. "If a problem is detected early on, an ergonomics and medical intervention can be taken to prevent a long-term problem from occurring," Radwin says. "Currently, most screening tests for carpal tunnel syndrome are not very specific, accurate or practical for routinely monitoring workers. In fact, there are none that are very good at all." The clinical test for carpal tunnel syndrome - called electromyography - is expensive and time consuming. It must be performed by a physician and its effects range from unpleasant to outright painful. In short, not many people would be willing to take it with the kind of frequency required for early detection of repetitive motion injuries. Radwin and his graduate students have developed two early detection instruments that are no more difficult to administer than a common hearing test. Just as workers in a loud factory receive periodic hearing checkups, workers who are exposed to vibrations, forceful exertions, stressful postures and repetitive motions can be tested regularly using the new method. In one test, subjects use their hands to feel for a small crack in a smooth metal plate. As the crack is enlarged by computer - from one tenth of a micron to several millimeters wide - workers run their fingers over the plate, respond-ing when they detect the gap. Because carpal tunnel syndrome dulls touch, sufferers tend to feel only the wider gaps. The other test is a simple video game that is controlled by squeezing bars together. "The patients we tested who have carpal tunnel syndrome use a lot more force than the people who don't have carpal tunnel syndrome symptoms and nerveconduction deficits," Radwin explains. That's because the median nerve tells your brain how hard you are squeezing and sends motor signals to the muscles in your fingers. "If there's an injury to the median nerve, that transmission of the nerve signals may be impaired," he says. Both devices are now being introduced to some workplaces, using employees as volunteers. In tests at UW Hospital and Clinics, both devices fared well at detecting known carpal tunnel syndrome sufferers, identified using electromyography. What isn't yet clear is whether the tests will help health care professionals ferret out the syndrome in its infancy.

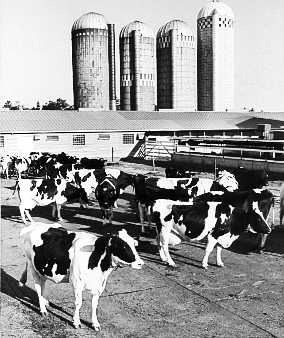

- For farmers: Help making hay

- Dairy researchers harness their work - from recommended cow diets to optimal barn ventilation - to help farmers beat problems and turn profits.

"About half the dairies we work with are experiencing severe financial problems. When we're able to turn some of these farms around, it's really gratifying."

remembers Robert Tulachka. "All the signs that were supposed to be there weren't there." The farm's veterinarian sought the assistance of a UW-Madison veterinary medicine professor, Kenneth Nordlund. The call led to a site visit from the veterinary medicine school's Food Animal Production Medicine program - and to the end of the mystery on the Tulachka farm.Nordlund's team ran through a checklist of medical tests on the cows and reviewed the nutritional content of their feed. They found the culprit: a condition called subacute rumen acidosis, the product of too much grain in the herd's diet. Tulachka says it "would have been very hard to recover" if the problem hadn't been corrected, but they haven't lost a single cow to illness since taking steps to improve their feed mix. The Food Animal Production Medicine program, run out of the School of Veterinary Medicine, has conducted as many as 80 such farm visits a year since its inception in 1989, offering farmers a combination of trouble-shooting and the latest in research knowledge. Veterinary science on farms is going beyond the traditional "barn calls" to treat the occasional sick cow, says veterinary medicine professor Gary Oetzel. The production medi-cine approach emphasizes total herd management, which can help prevent common problems like infectious disease before they start. The program's computer-assisted analysis of herd records can identify trends that might be sapping a farm's profit margin. Researchers run laboratory tests of feed ingredients to ensure the herd is getting the nutrients for optimal milk produc-tion. They can find environmental problems, such as poor barn ventila-tion, that can jeopardize the herd's health. "When you get into the nitty-gritty details during a herd investigation, you find issues that farmers have not considered before," Oetzel says. Subacute rumen acidosis is a good example. Excess acidity in the cow's system is caused by too much high-energy grain and too little forage food. This condition was poorly understood only a decade ago, but the UW program has become a leading source for diagnostic methods on this silent killer. "On the economic side, we're working on improving the marginal returns for farms," Oetzel says. "About half the dairies we work with are experiencing severe financial problems. When we're able to turn some of these farms around, it's really gratifying."